The Tone-Deaf Ear of the Law

Street performing is not uncommon in Japan’s larger cities. Many times it will take the shape of young people armed with instruments –usually guitars–, wailing their way through a crowded arcade like banshees. Yet the range is ample, and acts can include anything from shamisen players, classical string quartets and African djembes to painters and living statues. Much like the rest of the world, Japan is full of artists eager to show their craft, hopefully for a penny or two. Many are locals in search for their fifteen minutes of fame, others are travelling Japan and some are just looking for a quick yen. Yet busking doesn’t always turn out to be profitable. And like in the rest of the world, it can be a dangerous gig.

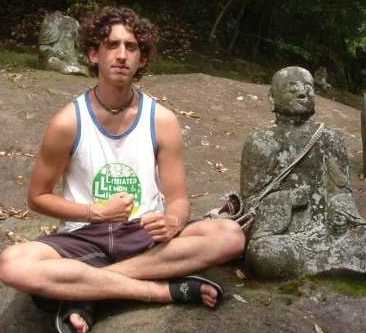

Robert Bertie has busked in over ten countries. A skilled sitar player, he is part of a band in Fukuoka, yet still enjoys the occasional foray into the streets at night. He has fond memories of welcoming audiences as well as darker ones of gangsters and abusive policemen. “Cops in the Basque country can be particularly brutal,” he says smiling. He tells me how he was the victim of a dramatic arrest in Vitoria for busking. “I wasn’t even getting money. They told me they didn’t like vagrants like me and arrested me on the spot. Luckily I didn’t spend the night in prison, but they did tell me to get out of town.” What about Japan? “It’s the same, though at least the police are much more polite here.”

Shinji, a street guitarist in Kumamoto, also thinks the police in Japan are not keen on his ilk. According to traffic laws, it is illegal to play music in any public street or park in the city. “They will tell me to put my guitar away and move on, but I just wait until they leave and play in a different place.” He knows what days and times to avoid, and though common lore is charged with urban myths and strange concepts –avoiding days ending in a certain number, for example–, he does a good job staying away from trouble. And he doesn’t think he is doing anything wrong by playing his guitar.

Street performers have for centuries been stigmatised as vagrants, bums or criminals by the authorities, either as disturbers of the public peace at best or petty thieves at worse. It is an age-old prejudice, spawning from itinerant Gypsy tribes in Europe to the “floating world” artists of the Edo period. Perhaps there is something unruly, defiant even, about people expressing themselves in public.

Although there is a chance that a minority of street performers may sometimes resort to dirty deeds, the authorities generally fail to see is that artists are just as, if not more, vulnerable to crime than others. It is the gangsters and petty criminals who typically hound street artists for protection money and not the other way round. “I was harassed by gangsters in Amsterdam once,” says Bertie. Japan doesn’t seem to be the exception, although the mafia has never approached him personally.

On a weekly night raid, a Kumamoto police inspector confirms these doubts. In his view, performers work hand in hand with the mafia to conduct “illegal business practices in public areas.” After asking for my alien registration card and jotting down my personal information, he is quick to inform me about the recent arrest of several street vendors selling counterfeit goods (allegedly, for the Yakuza). “But surely performers are different. They aren’t selling anything – people decide to give them money on their own accord,” I argue. To no avail, of course. “Traffic laws say it is illegal to play music in public areas. Anyway, I’m just doing my job. Where did you say you work again?”

Just like Shinji, the buskers will wait until the wolves are gone before they start playing again. Soon the streets are filled with music other than the strident clatter of Pachinko parlours and amphetamine J-Pop. It’s another night in the city and the coast looks clear. For the time being, at least.

Street performing is not uncommon in Japan’s larger cities. Many times it will take the shape of young people armed with instruments –usually guitars–, wailing their way through a crowded arcade like banshees. Yet the range is ample, and acts can include anything from shamisen players, classical string quartets and African djembes to painters and living statues. Much like the rest of the world, Japan is full of artists eager to show their craft, hopefully for a penny or two. Many are locals in search for their fifteen minutes of fame, others are travelling Japan and some are just looking for a quick yen. Yet busking doesn’t always turn out to be profitable. And like in the rest of the world, it can be a dangerous gig.

Robert Bertie has busked in over ten countries. A skilled sitar player, he is part of a band in Fukuoka, yet still enjoys the occasional foray into the streets at night. He has fond memories of welcoming audiences as well as darker ones of gangsters and abusive policemen. “Cops in the Basque country can be particularly brutal,” he says smiling. He tells me how he was the victim of a dramatic arrest in Vitoria for busking. “I wasn’t even getting money. They told me they didn’t like vagrants like me and arrested me on the spot. Luckily I didn’t spend the night in prison, but they did tell me to get out of town.” What about Japan? “It’s the same, though at least the police are much more polite here.”

Shinji, a street guitarist in Kumamoto, also thinks the police in Japan are not keen on his ilk. According to traffic laws, it is illegal to play music in any public street or park in the city. “They will tell me to put my guitar away and move on, but I just wait until they leave and play in a different place.” He knows what days and times to avoid, and though common lore is charged with urban myths and strange concepts –avoiding days ending in a certain number, for example–, he does a good job staying away from trouble. And he doesn’t think he is doing anything wrong by playing his guitar.

Street performers have for centuries been stigmatised as vagrants, bums or criminals by the authorities, either as disturbers of the public peace at best or petty thieves at worse. It is an age-old prejudice, spawning from itinerant Gypsy tribes in Europe to the “floating world” artists of the Edo period. Perhaps there is something unruly, defiant even, about people expressing themselves in public.

Although there is a chance that a minority of street performers may sometimes resort to dirty deeds, the authorities generally fail to see is that artists are just as, if not more, vulnerable to crime than others. It is the gangsters and petty criminals who typically hound street artists for protection money and not the other way round. “I was harassed by gangsters in Amsterdam once,” says Bertie. Japan doesn’t seem to be the exception, although the mafia has never approached him personally.

On a weekly night raid, a Kumamoto police inspector confirms these doubts. In his view, performers work hand in hand with the mafia to conduct “illegal business practices in public areas.” After asking for my alien registration card and jotting down my personal information, he is quick to inform me about the recent arrest of several street vendors selling counterfeit goods (allegedly, for the Yakuza). “But surely performers are different. They aren’t selling anything – people decide to give them money on their own accord,” I argue. To no avail, of course. “Traffic laws say it is illegal to play music in public areas. Anyway, I’m just doing my job. Where did you say you work again?”

Just like Shinji, the buskers will wait until the wolves are gone before they start playing again. Soon the streets are filled with music other than the strident clatter of Pachinko parlours and amphetamine J-Pop. It’s another night in the city and the coast looks clear. For the time being, at least.

2 comments:

play on you busker

Post a Comment