O RotAryan!

I've just come back from a billionaire's lunch, feeling completely stiff and out of place. I did, however, look 'hot' in my suit, or so I was told. (It certainly felt that way - leave it to posh hotels to crank up the heating at full blast for no reason). If only they knew my suit only sees the light of day a few times a year, usually for funerals, and most recently for a couple of weddings I conducted.

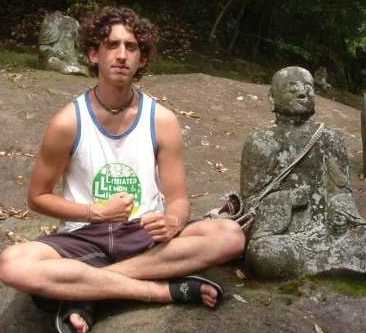

So how did Alex Holmes, language teacher, part-time bum, occasional fake priest, long-haired stoner, frustrated writer and fiddler of discrete musical abilities manage to get invited to an Old Boys Lunch? Given Japan's near-obsessive compulsion with "the outside" (it could be said, just to give legitimacy to its racialist "inside"), Kumamoto must be dying for something "international," if only to shake its nagging feeling of provincial inferiority. As the only Chilean in the city, I fit the international leather shoes quite well. Japan certainly puts the "national" in "internationalisation," and more often than not I am required to act as a poster boy for it. I would have a hard time believing that in any other country they would pay a lowlife like me almost 30 pounds for just for a 3 minute interview in front of sleeping old men, some with with egos as overinflated as their wallets.

The lunch started in a rather bipolar fashion. First, there was a standing up rendition of Kimigayo, the nationalist Japanese anthem used in WWII. As the people around me sang gravely, hands on their chests, full of pride and contempt for history, I was transported to my school days under Pinochet's rule and his addendum to the national anthem: "Vuestros nombres valientes soldados, que habeis sido de Chile el sosten..." (Thy names, brave soldiers, who have been Chile's great pillars.") A man next to me gripped a pamphlet for a new Japanese film titled "Men's Warship Yamato," a Leni Reifenstahl-esque movie about a Japanese submarine during the war. I'd seen it all before. After all, authoritarianism is usually based on propaganda, and the latter is invariably tied with kitsch. Silence is usually the best remedy in these situations, and so I stood there, quietly scratching my arm.

Soon, the mood changed and the Club anthem began playing, a jumpy hymn based on the slogan "service above self." The clumsy piano and the morally-charged lyrics were vaguely reminiscent of many a children's song from communist youth camps. Self-sacrifice for the sake of a higher ideal is as pure an endeavour as it is easily distorted by the powers that be. The Japanese establishment places a high regard on purity: purity of thought, of action, of spirit. Dying for the Emperor was nothing but the purest form of obedience, of militarist avowal to the fact that He knew better. Neither Hitler, Stalin, Pinochet nor Mao departed radically from this idea: serving a higher goal pertaining to their assumptions of the public good, carried out even in spite of the public itself. The club's anthem smacked of well concealed despotism under the guise of well meaning altruism. The heartfelt rendition of Kimigayo moments earlier gave the scene an even creepier highlight. Here were the two extremes of authoritarianism, clasping hands in musical communion. It was endearing, for lack of a better word.

The songs were followed by a few quick speeches, and soon I was in front of the mic, talking about sea turtles and thatch cutting in Shikoku. (Volunteering is something Japanese audiences love to hear about, perhaps because it meshes well with the right wing's ingrained ideals of masochistic self-sacrifice). I might have clumsily overstepped the boundary, however, as I mentioned how people conduct illegal businesses with endangered turtle shells. There was some shuffling in the audience, others coughed, and others looked away in seeming discomfort. Maybe something in them stirred, a little speck of conscience biting where it hurts - for all they know they could be the biggest poachers themselves. The announcer quickly thanked me, and my turn was over. A man took my place and started talking about his love of chicken breasts for nearly 25 minutes.

As soon as I came back home, my housemate asked me if I had made any good connections. I cannot say for sure. While I did meet some interesting characters, I was introduced to many others whom I have no idea what they do, apart from the fact that they may well belong to the corporate forces of Evil. And I couldn't go around giving the business card I usually give my friends, the one that says "Paul Fontecilla, Escort, lover and drain repairman, all your plumbing needs delivered." They might never call me. But then again, the power of "internationalisation" might prove stronger, and my rumbling stomach may yet score some more free lunches on their tab.