El Amigo

For a little black humour follow this link to a short script I wrote. (English version to come soon).

Saturday, October 29, 2005

Thursday, October 27, 2005

The Better Man

The Better ManThe idealistic fires of my anarcho-syndicalist side have been all but fanned as of late. With every passing day, I get more and more convinced of the futility of money for the sake of it.

I just finished reading a short story by Tolstoy called "The Death of Ivan Illych," and it really struck a nerve with something going around my head lately. At the risk of making this sound like a book report, the character is a lawyer who dies lonely in a rich house, accompanied by his estranged wife and his selfish children, his only pleasure resting his feet on an innocent peasant boy's shoulders to relieve the agony of the illness eating away his life. (It's pretty evident that the Russian realists weren't the chirpiest birds in the nest). And yet, the story is an examination of how Illych's life was over long before that, overdosing on an immoral cocktail of wealth, greed and power. In fact, the character is only redeemed after he acknowleges that his life, albeit pleasant, was not a good one. "But oddly enough none of those best moments of his pleasant life now seemed at all what they had seemed at the time," explains Tolstoy at the turning point of Ivan's illness, who begins a much belated introspection only after admitting to himself that he will die soon. It might be a tad extreme and melodramatic, but who can say this scenario is strange to those who consciously live at the expense of others, forgoing virtue for social standing and a facade of success?

Then there's a Pearl Jam song I really like, mostly due to the lyrics (but also because of its cooky ukelele rhythm):

"Sorry is the fool who trades his soul for a corvette,

Thinks he'll get the girl he'll only get the mechanic.

What's missing? He's living a day he'll soon forget.

That's one more time around. The sun is going down,

The moon is out but he's drunk and shouting,

Putting people down. He's pissing. He's living a day he'll soon forget.

Counts his money every morning. The only thing that keeps him horny.

Locked in a giant house that's alarming. The townsfolk they all laugh.

Sorry is the fool who trades his love for hi-rise rent.

Seems the more you make equals the loneliness you get.

And it's fitting. He's barely living a day he'll soon forget.

That's one more time around and there is not a sound.

He's lying dead clutching Benjamins, never put the money down.

He's stiffening. We're all whistling a man we'll soon forget."

Lastly, there's this arsehole engineer I met at Jeff's bar the other night. He asked me about my job, and when I told him I was a teacher he gave me the most disgustingly condescending smirk. "Oh, so you're still doing /that/" he said, as though I was a complete loser for not getting an 'important' job at a so-and-so 'respectable' company like his. I really felt like bashing his teeth in. I just smiled, however, and proceeded to explain how great it feels to see your students learn things, and how teaching can be a million times more fulfilling than sitting at a desk all day, just so you can get bits of paper to exchange for shiny trinkets.

So much for unimportant jobs.

Sunday, October 23, 2005

The Untree

The Untree6:51am. The early minutes after a turbulent few hours of those introspective nights, when one tumbles and turns and pretends to sleep, unconsciously conscious of the changing shades of dawn, clamped away from stupor by delusions of self-absorbed paranoia spawned by imaginary turntables and Marcel Duchamp inside Magritte's non-pipe.

Yesterday I had bought myself a set of watercolours and spent some time making an uninteresting picture of a badly drawn tree. Leafless, it sucks earth from the ground, as though the two were a single peculiar entity, protruding from the brown soil like a pimple or a nipple, or a rotting cauliflower. Among the inexplicable hues there are infinitesimal hints of red and green. The branches are black, and the trunk is of sandy sienna – hence its resemblance to the dirt below. The sky remains unpainted. In my mind it blends with the leaves -the ones that have fallen- and earth and firmament are one; the moon exclaims "Bismillah!" and the tree remains but that, standing passive in the centre and gaping back at me.

So, despite the pretentiousness of baptism, it is now called "the Untree," homage to the silhouette of a Danish madman reflected in the shadows of a cave. It is my tricolour flag of brown, browner and yellow screaming chants of revolution, and the fifty stars that are not there represent all of mankind's sins: sleepiness, insomnia, unruly hair, boils in the mouth. And then, when the bell rings seven times, one will suddenly remember that the sky lingers unpainted and that suddenly it's time for breakfast and that the tree that stands so tall and flat in grainy paper is not, and never was, a tree.

Friday, October 21, 2005

The Perfect Two

When I was about ten, we had these multicoloured copybooks for different school subjects, all with the school insignia on the front. Science was orange, social studies was blue, Spanish was red, English, yellow, and maths was green. Of all these, it was usually my maths copybook which would be the most disorderly, numbers jotted down everywhere in all kinds of pens and pencils - I had a penchant for losing them all the time (and I've kept it ever since). The pages, originally pristine white with subtle light-blue lines, would fall like city snow, showing the murky grayish-brown marks left by a thousand erasers gone astray. My green copybook was, in short, a complete mess.

That is why it was so strange when the perfect two decided to visit me there.

One day, in between many dishevelled calculations (fractions, I think), the teacher was writing some exercises on the board when it happened. Her numbers were not particularly beautiful -in fact, not even memorable enough for me to remember precisely. They were, however, legible and well-crafted. And compared to my own, they were like the roof of the sixteenth chapel is to crass graffiti on a restaurant napkin. Her numbers were purely functional, no more and no less, written with that purpose in mind and living for it to the bitter, eraserbound end.

This one number, however, was different. I would later come to believe its origin was only halfway in the reality of perfect logic, while its other feet were half set in alternate dimensions of universal inspiration. And there was no prelude either, no fanfare, no sudden bout of artistic inspiration: it just happened, quickly and destitute of thought, much like every other answer in my maths exercises. As I squiggled along my increasingly incorrect fractions, the two came out of nowhere. Before I knew it, it posed itself in my grotesque green copybook, a single shining pearl within murky oceans of geometrical water.

Here stood the most perfect number two ever made by man. The main strokes were marked with calm precision, not too hard on the paper and not too soft, regular all throughout with no blemishes of tardiness or hurry. Its fancy plumage was the upper curve, arousing in its voluptuousness, yet affectionate in its sweet caresses to the paper below. The line beneath curved up, ever so slightly, in perfect balance with its sister above.

Quickly, I tried to copy it several times. "This," I thought to myself, "will be my newly adopted shape for number two." And every time I would fail. For weeks I couldn't stop thinking about it. Every time I pulled out my green copybook, I would turn the pages, holding my breath in expectant hesitation, just to admire its perfect figure one more time. Again, I would try to copy it, and every time my efforts would be foiled. Meanwhile, the perfect two just giggled back as I tried to steal away its glory, safe in the knowledge that it was the only and last perfect number to set foot on any of my notebooks, my hands too clumsy to recreate it and my mind too aware to picture it. The two was spawned from nothing, as in direct opposition to the physical laws, ex nihilo nihil est, and the very knowledge of its existence negated every possibility of its rebirth.

That green copybook stayed with me for years after its pages had run out and the fractions inside became a childish joke. Every so often it would resurface from the debris of my bedroom clutter, and when it did, I was quick to check that one page of unsurpassed dual beauty. And one day, as the copybook finally found its way to stationary heaven, the perfect two disappeared from human sight forever.

I never showed it to anyone, of course. This knowledge alone was my own possession. Beauty was only true because it was imaginary, like the mold carved faithfully in my dirty maths book. Even trying to share this would have been futile, with more than one blank stare to mar my enthusiasm.

I still think about the perfect two. And it has also tried to come back. Many times it will make a coy entrance in an unsuspected place: a receipt, a foreign bank note, a date on a chalky blackboard. But whenever it happens I realise that these are only copies, an aftershock of the original, like a cranky stone making slow ripples on a pond. All I do is compare it to the mold and I know this new version, not matter how alluring, is ultimately inferior. I glanced at perfection once, and now the real perfect two lives outside my grasp. It will live telling me that because of itself it may never be seen again, and I'll know that the blessing of its beauty was also the beauty of its curse.

When I was about ten, we had these multicoloured copybooks for different school subjects, all with the school insignia on the front. Science was orange, social studies was blue, Spanish was red, English, yellow, and maths was green. Of all these, it was usually my maths copybook which would be the most disorderly, numbers jotted down everywhere in all kinds of pens and pencils - I had a penchant for losing them all the time (and I've kept it ever since). The pages, originally pristine white with subtle light-blue lines, would fall like city snow, showing the murky grayish-brown marks left by a thousand erasers gone astray. My green copybook was, in short, a complete mess.

That is why it was so strange when the perfect two decided to visit me there.

One day, in between many dishevelled calculations (fractions, I think), the teacher was writing some exercises on the board when it happened. Her numbers were not particularly beautiful -in fact, not even memorable enough for me to remember precisely. They were, however, legible and well-crafted. And compared to my own, they were like the roof of the sixteenth chapel is to crass graffiti on a restaurant napkin. Her numbers were purely functional, no more and no less, written with that purpose in mind and living for it to the bitter, eraserbound end.

This one number, however, was different. I would later come to believe its origin was only halfway in the reality of perfect logic, while its other feet were half set in alternate dimensions of universal inspiration. And there was no prelude either, no fanfare, no sudden bout of artistic inspiration: it just happened, quickly and destitute of thought, much like every other answer in my maths exercises. As I squiggled along my increasingly incorrect fractions, the two came out of nowhere. Before I knew it, it posed itself in my grotesque green copybook, a single shining pearl within murky oceans of geometrical water.

Here stood the most perfect number two ever made by man. The main strokes were marked with calm precision, not too hard on the paper and not too soft, regular all throughout with no blemishes of tardiness or hurry. Its fancy plumage was the upper curve, arousing in its voluptuousness, yet affectionate in its sweet caresses to the paper below. The line beneath curved up, ever so slightly, in perfect balance with its sister above.

Quickly, I tried to copy it several times. "This," I thought to myself, "will be my newly adopted shape for number two." And every time I would fail. For weeks I couldn't stop thinking about it. Every time I pulled out my green copybook, I would turn the pages, holding my breath in expectant hesitation, just to admire its perfect figure one more time. Again, I would try to copy it, and every time my efforts would be foiled. Meanwhile, the perfect two just giggled back as I tried to steal away its glory, safe in the knowledge that it was the only and last perfect number to set foot on any of my notebooks, my hands too clumsy to recreate it and my mind too aware to picture it. The two was spawned from nothing, as in direct opposition to the physical laws, ex nihilo nihil est, and the very knowledge of its existence negated every possibility of its rebirth.

That green copybook stayed with me for years after its pages had run out and the fractions inside became a childish joke. Every so often it would resurface from the debris of my bedroom clutter, and when it did, I was quick to check that one page of unsurpassed dual beauty. And one day, as the copybook finally found its way to stationary heaven, the perfect two disappeared from human sight forever.

I never showed it to anyone, of course. This knowledge alone was my own possession. Beauty was only true because it was imaginary, like the mold carved faithfully in my dirty maths book. Even trying to share this would have been futile, with more than one blank stare to mar my enthusiasm.

I still think about the perfect two. And it has also tried to come back. Many times it will make a coy entrance in an unsuspected place: a receipt, a foreign bank note, a date on a chalky blackboard. But whenever it happens I realise that these are only copies, an aftershock of the original, like a cranky stone making slow ripples on a pond. All I do is compare it to the mold and I know this new version, not matter how alluring, is ultimately inferior. I glanced at perfection once, and now the real perfect two lives outside my grasp. It will live telling me that because of itself it may never be seen again, and I'll know that the blessing of its beauty was also the beauty of its curse.

Wednesday, October 12, 2005

Las Décimas de Respuestas

In response to Sebastian Jatz's epic poem (hopefully a link will be posted soon)

Buen día iñor Pezgato

que su' décimas le leí

y que nunca antes vi

tan jocosamente escrita

pasándome un buen rato

con lo cierto 'e su relato

¡Qué verdades, por la chita!

Me disculpa la demora

el tiempo se me fragmenta

planté arroz y no polenta

en campo menos eliseo

Ahí se pasa ben la hora

sin cemento, que en Gomorra

¡Por la chita, aquí es re-feo!

Bien gueno me parece

el que observe usté a esa gente

que aunque no esta toa demente

es mesmita a la de aca

desconfiaos los ingleses

donde el hielo da intereses

¡Por la chita, que es maleá!

Allá en London toman té

acá el mesmo está de verde

y si la soledad les muerde

bloody hell o kakekó

el sonido que más se ve

de la cerveza o del saké

¡Chitas, ya nos embriagó!

En la cueca que le toque

quizás haya una lección

que al final el conrazón

se lo dicta a cual su hogar

está todo en el enfoque

tenedor o palitroque

¡Chitas, que nos da pa' hablar!

Ya ve usté querido iñor

que al final es todo igual

lo distinto, superficial

Zulu, Chino, Chango, Chiita

conviviendo así es mejor

como usté, con buen humor

¡Somos gente, por la chita!

In response to Sebastian Jatz's epic poem (hopefully a link will be posted soon)

Buen día iñor Pezgato

que su' décimas le leí

y que nunca antes vi

tan jocosamente escrita

pasándome un buen rato

con lo cierto 'e su relato

¡Qué verdades, por la chita!

Me disculpa la demora

el tiempo se me fragmenta

planté arroz y no polenta

en campo menos eliseo

Ahí se pasa ben la hora

sin cemento, que en Gomorra

¡Por la chita, aquí es re-feo!

Bien gueno me parece

el que observe usté a esa gente

que aunque no esta toa demente

es mesmita a la de aca

desconfiaos los ingleses

donde el hielo da intereses

¡Por la chita, que es maleá!

Allá en London toman té

acá el mesmo está de verde

y si la soledad les muerde

bloody hell o kakekó

el sonido que más se ve

de la cerveza o del saké

¡Chitas, ya nos embriagó!

En la cueca que le toque

quizás haya una lección

que al final el conrazón

se lo dicta a cual su hogar

está todo en el enfoque

tenedor o palitroque

¡Chitas, que nos da pa' hablar!

Ya ve usté querido iñor

que al final es todo igual

lo distinto, superficial

Zulu, Chino, Chango, Chiita

conviviendo así es mejor

como usté, con buen humor

¡Somos gente, por la chita!

Monday, October 10, 2005

The Caffeine Factor

I remember watching a series of TV adverts for a certain brand of instant coffee a few years ago. In them, the protagonist would follow a series of random events leading to different adventures, each one wackier than the next, such as bungee jumping, playing poker with Colombian drug lords, landing an airplane and so on. No matter how faint the actual connection to instant coffee, at the end the hero would invariably sip a hot mug, and a legend would pop up claiming that "one thing leads to the next." I thought it mass-produced corporate glamour at its best.

I remember watching a series of TV adverts for a certain brand of instant coffee a few years ago. In them, the protagonist would follow a series of random events leading to different adventures, each one wackier than the next, such as bungee jumping, playing poker with Colombian drug lords, landing an airplane and so on. No matter how faint the actual connection to instant coffee, at the end the hero would invariably sip a hot mug, and a legend would pop up claiming that "one thing leads to the next." I thought it mass-produced corporate glamour at its best.

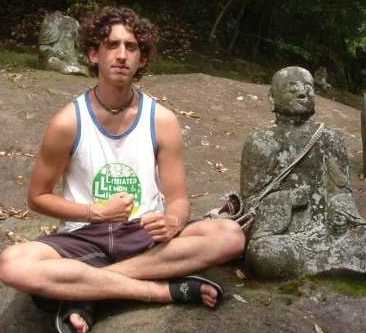

On Saturday afternoon I met up with some hitchikers at a Starbucks. We quickly befriended each other, so I decided to guide them around Kumamoto. We strolled around town and visited a temple. Come the evening we had a smoke and went for a few drinks. Before I knew it the sun shone straight over our heads. What's more, we had boarded a ferry and stood in the Shimabara peninsula eating french toast.

That evening we made it to some waterfalls, a hot spring next to the sea and finally Nagasaki, where we witnessed a drunken ex-yakuza thrusting his pelvis frenetically while shouting "hard gay!" at the port. One of my new friends strummed his guitar, ad-libbing about taking a dump in the fields. Another two consumed a variety of energy drinks, Black/Black branded caffeine gum and a vast array of legal stimulants available over the convenience store counter. Another played the harmonica, and hard gay danced some more. Finally, at a Spanish Art exhibition on Monday afternoon, Dali and Piccasso themselves hit the final surreal note with some of their minor works.

Later in the evening, on the ferry back to Kumamoto, I caught a glimpse of my reflection on a window. It smiled back at me, sipping a cold can of vending machine coffee.

*Picture taken by Tim.

I remember watching a series of TV adverts for a certain brand of instant coffee a few years ago. In them, the protagonist would follow a series of random events leading to different adventures, each one wackier than the next, such as bungee jumping, playing poker with Colombian drug lords, landing an airplane and so on. No matter how faint the actual connection to instant coffee, at the end the hero would invariably sip a hot mug, and a legend would pop up claiming that "one thing leads to the next." I thought it mass-produced corporate glamour at its best.

I remember watching a series of TV adverts for a certain brand of instant coffee a few years ago. In them, the protagonist would follow a series of random events leading to different adventures, each one wackier than the next, such as bungee jumping, playing poker with Colombian drug lords, landing an airplane and so on. No matter how faint the actual connection to instant coffee, at the end the hero would invariably sip a hot mug, and a legend would pop up claiming that "one thing leads to the next." I thought it mass-produced corporate glamour at its best.On Saturday afternoon I met up with some hitchikers at a Starbucks. We quickly befriended each other, so I decided to guide them around Kumamoto. We strolled around town and visited a temple. Come the evening we had a smoke and went for a few drinks. Before I knew it the sun shone straight over our heads. What's more, we had boarded a ferry and stood in the Shimabara peninsula eating french toast.

That evening we made it to some waterfalls, a hot spring next to the sea and finally Nagasaki, where we witnessed a drunken ex-yakuza thrusting his pelvis frenetically while shouting "hard gay!" at the port. One of my new friends strummed his guitar, ad-libbing about taking a dump in the fields. Another two consumed a variety of energy drinks, Black/Black branded caffeine gum and a vast array of legal stimulants available over the convenience store counter. Another played the harmonica, and hard gay danced some more. Finally, at a Spanish Art exhibition on Monday afternoon, Dali and Piccasso themselves hit the final surreal note with some of their minor works.

Later in the evening, on the ferry back to Kumamoto, I caught a glimpse of my reflection on a window. It smiled back at me, sipping a cold can of vending machine coffee.

*Picture taken by Tim.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)